There’s a lot of reasons people don’t finish a race: blisters, nutrition failures, illness, and the like. We try our best to account for them all, but some things are just out of our control. Oregon Cascades 100 was supposed to be our first 100 mile race. But, with the Flat Fire raging outside Sisters, Oregon, we are lucky to even toe the line.

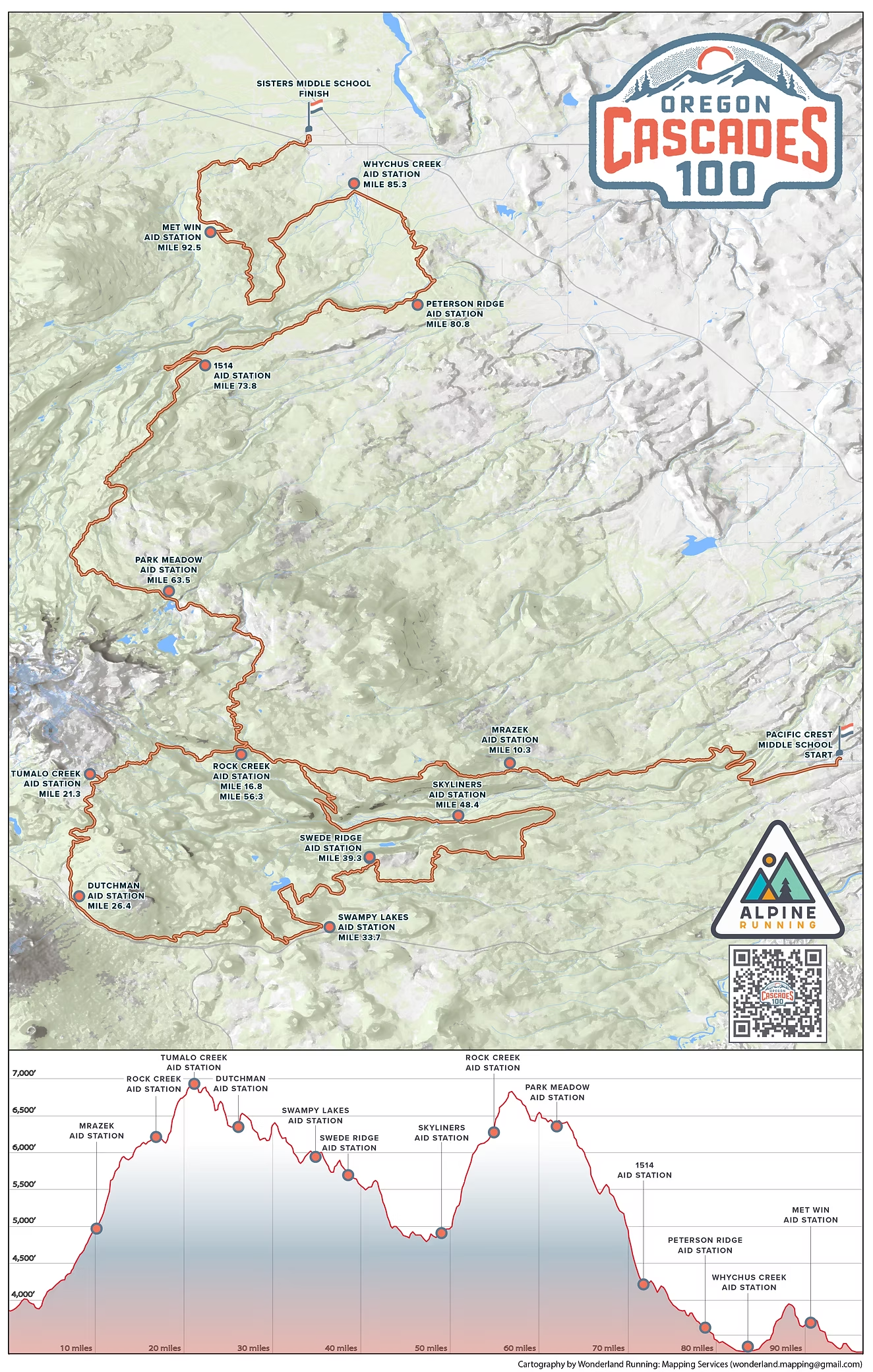

We chose Oregon Cascades 100 for it’s scenic views, moderate climbs (12,000 feet of climbing over 100 miles), and support capabilities. The course winds from Bend to Sisters, Oregon, with two sustained but still runnable climbs, and soft flowy trail. Having run a decent range of races up to this point, we also appreciate the benefits of a larger scale race with more infrastructure to handle emergencies and last minute changes. For our first 100 miler, Alpine Running’s long track record in the area is compelling.

Aid Stations

| Mileage* | Distance to Next Aid Station | Crew | Drop Bags | Bathroom | Cut Off | Pacer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Start | 0 | 10.3 | |||||

| AS 1 – Mrazek | 10.3 | 6.5 | No | No | No | ||

| AS 2 – Rock Creek | 16.8 | 4.5 | No | No | No | ||

| AS 3 – Tumalo Creek | 21.3 | 5.1 | No | No | No | ||

| AS 4 – Dutchman | 26.4 | 7.3 | Yes | No | Yes | ||

| AS 5 – Swampy Lakes | 33.7 | 5.6 | Yes | Yes | Yes | 10.5 | Yes >60 |

| AS 6 – Swede Ridge | 39.3 | 9.1 | No | No | No | ||

| AS 7 – Skyliners | 48.4 | 7.9 | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| AS 8 – Rock Creek | 56.3 | 7.2 | No | No | No | ||

| AS 9 – Park Meadow | 63.5 | 10.3 | No | No | No | 21 | Yes |

| AS 10 – 1514 | 73.8 | 7 | Yes | Yes | Yes | 24 | Yes |

| AS 11 – Peterson Ridge | 80.8 | 4.5 | No | No | No | 26 | |

| AS 12 – Whychus | 85.3 | 7.2 | Yes | No | Yes | 27.5 | Yes |

| AS 13 – Met Win | 92.5 | 6 | Yes | No | No | 30 | Yes |

| Finish | 98.5* | 32:01:18 |

Training for Oregon Cascades

Of course, best laid plans and all… We start preparing for this race in early spring with progressively longer races to test our techniques before Oregon Cascades. We start with Snaketail on April 12th, learning a lot about running through wet environments and focusing on liquid nutrition. I experience a bit of a misadventure at Strolling Jim 40 in May, with a lot of speed work and 3rd place at the cost of my left foot. By the time I can run again, I gingerly toe the line for Night Howler 50 on June 28, where we test out lighting and other practical considerations while running through the night. That leaves us with a final two month ramp up before flying out to Oregon.

Days Before the Race

A week before the event, we get the first inklings that this race will not go down as intended. Weather reports predict highs in the low nineties. We update wardrobe and double down on our hydration plans. But we don’t realize the true environmental threat until our first night in Bend.

The smoke fills the rental in the early morning hours as a shifting wind blow a hazy front from the Flat Fire, still in it’s early stages. When we wake up, the rental is permeated but another shift in the wind means that, outside, the sky is clear and air fresh. We are worried but remain cautiously optimistic as we arrange our gear.

That only lasts until we head west to Sisters.

The Flat Fire

Ash rains down at the bag drop the day before the race. The smoke is thick and continues to worsen by the time we pick up our bibs, shirts, and head back out. It is a sobering reality check. Throughout the day and into the night, the race director updates us on the race status.

We wanted to send an update on the Flat fire that started yesterday evening. First, the fire is not near the course. It is located near Culver. The fire itself is not impacting the course. The potential for smoke into the area is what we are monitoring. Due to the fact this is a point to point course, the AQI can vary widely. Typically the higher parts of the course can have a better air quality with smoke settling in the valleys/in town. We have had smoke before while course marking only for the winds to shift and blue skies for race day. AQI can change hourly. The forecast currently looks favorable and reports from up the course are good this morning. We will proceed with check in today and continue to monitor the AQI.

Oregon Cascades 100

To our minds, the likely hood of even starting is low, but we also know that Bend mornings have been clear, thus far. So we move forward as if the race is on.

Race Day

At 4:31 AM, we finally have the go ahead: “We are a GO! We have seen AQI improvement and are moving forward. See you all at the start line in Bend! “

Aside from the looming threat of the fire, everything seems to fall into place. We tape our feet the night before to mitigate against blisters. Our hydration vests are packed, our outfits laid out. We wake up at 4AM, wolf down a quick breakfast of Cream of Wheat with berries, and dress. We even have time to talk through our strategy before heading out to the start line and a clear, glorious sunrise.

Photography by James Holk for Alpine Running

The sky is clear as we surge forward at 6AM with 300 other runners. The first two miles are paved road with a following 2 miles of gravel before turning of onto soft, smooth, dusty single track. We climb through pine forests for 20 miles to peak at Tumalo Creek Aid Station in the late morning. Most of the incline is incredibly runnable. We only slow to a walk on some of the later inclines out of caution not to wear ourselves out too early.

The descent is a delight as we surrender to gravity and ride a rollercoaster of dirt bike trails for the next thirty miles. Dutchman Aid Station at mile 26.4 is where we first see crews. Not ours, but others who cheer for every runner entering and leaving the Aid Station. It’s an amazing pick-me-up as we feel the day beginning to heat up.

Photography by James Holk for Alpine Running

Photography by James Holk for Alpine Running

Swampy Lakes Aid Station

Our crew surprises us at Swampy Lakes Aid Station at mile 33.7. While this aid station is notorious for their popup bar where volunteers attempt to ply the runners with liquor, we focus on water, ice, coke, and cookies. It’s only fair to note that this aid station also boasts some solid hamburgers, but there is no way I could stomach a heavy lunch in this heat.

By this point, my sides are terribly chaffed from my hydration pack and Chris feels a hot spot on his toe. While crew helps Chris with his foot, others help me clean the salt and sweat from my sides and apply bandages to protect against further chaffing.

After sitting to work on his foot, it takes a while for Chris’s legs to loosen up as we leave the aid station and climb a slightly more exposed section of trail. Usually, we are far more efficient at aid stations, but being our first 100 miler, we are trying to be hyper vigilant when it comes to foot care.

Swede Aid Station (Mile 39.3)

Maybe we should have been more concerned about tummy troubles because, by the time we reach Swede Aid Station, Chris is having a hard time identifying anything that he can contemplate eating. I grab some cookies and focus on ice. Ice in my buff. Ice in my hat. Ice in all three of my drink bottles. This next stretch is 9 miles through the heat of the day and I easily emptied two bottles in the last 5.6 mile stretch. So, three bottles it is and I am grateful for each.

We munch away as we walk out of the aid station for the first quarter mile. But soon we are running. This proves to be the most runnable and smooth downhill section sinces the first four miles of roads. Even as we cross an exposed section where the majority of trees are felled and many other runners walk in the heat, our training in the Tennessee humidity finally justifies itself. We drop onto forest roads and stretch our legs, side-by-side.

A couple miles outside of Skyliners, we round a ridgeline and get a wiff of things to come. The air is hazy with smoke and the concerns of the morning return. This is a significant amount of smoke. How much worse can it get? We are approaching the evening, when winds shifts. But to whose favor?

Skyliners Aid Station

You may be excused for any confusion as to wether we stopped at an aid station or a spa when we roll into Skyliners. Our crew has a footbath of epsom salts where Chris soaks his feet while I manage the turnover of our gear from the day arrangement to our night equiptment and restocking our nutrition. Despite the pervasive haze of smoke, we get a little too comfortable, whiling away over half an hour in seats.

It takes a while for our legs to loosen out and run again. Even so, our running is limited, because this next section includes 1,400 ft of elevation gain over 8 miles. Much of it is an incline that we might have run in the first half of the race, but we are conserving our energy for the remaining 40 miles to go.

Rock Creek Aid Station

Rock Creek Aid Station is the only Aid Station that we visit twice, each time as a herald of a near summit. We quickly refill our bottles, ice, and move on for the last two miles of climbing. By this time, our legs are thrashed and we walk even mild uphills. But, as soon as the trail turns downward, we surrender to elevation and charge down the trail.

Here, winding along the peak of our race, the sky shifts into blazing pinks and reds as the sun sets through wildfire smoke. It’s brilliant and ominous. But at this elevation and on the other side of the ridge, we aren’t noticing the smoke as much.

I am haunted by the sounds of an Aid Station that always seems just ahead. We hear cowbells, cheers, but dusk settles in an we still aren’t at that Aid Station. We held off unpacking our lights, expecting to arrive at the aid station, so it’s truly night by the time we pause to pull out or lights and turn onto a forest road.

Photography by Tiare Bowman for Alpine Running

Park Meadows Aid Station

We are worried that we missed the aid station. When we finally turn a corner and see the lights of Park Meadows Aid Station. There is even someone in the road to meet us. But it’s not what we’re expecting: this is the aid station manager. She tells us that race is cancelled. We need to vacate the course.

There’s already around twenty runners waiting at the aid station for crews to pick them up. We have no cell service and are unsure that our crew could pick us up even if we could reach them. Fortunately, a couple with a van offer us a ride and we gladly drive down the mountain to the Sisters and the race finish.

Half way down the Mountain I have cell service and call our crew to notify them that we’ll need a pick up at Sister’s Middle School. We gather with other runners at the track, bewildered and unsure about the outcome.

Photography by James Holk for Alpine Running

After Oregon Cascades 100

The next morning dawns clear and smoke free in Bend, Oregon. Given that we only got to run two thirds of the 100 mile race that we trained for, our legs are in relatively good shape. Stairs might be an ordeal but the general business of the day is just a little more stiff and awkward.

No new black toenails.

Fewer than usual blisters for a distance that far.

A glaringly absent belt buckle.

And roiling sense of inner conflict.

Yes, I’m bummed that we could not finish the race. But I’m also grateful that we got to start. No race director wants to run a race during a wild fire, but Alpine Running attempted to thread a very fine needle between meeting expectations and protecting runners, crew, and volunteers. People will litigat this race to death. Both by those who feel the oragnizers should have allowed them to keep running and those who feel the organizers should have cancelled the race earlier. Personally, I think the anger on both sides demonstrates the impossible situation any race director finds themselves in the wake of a natural disaster.

My heart goes out to all those affected by the fire. The grievances of us runners are so minor in comparison.

Photography by James Holk for Alpine Running

Photography by James Holk for Alpine Running

Race Analysis

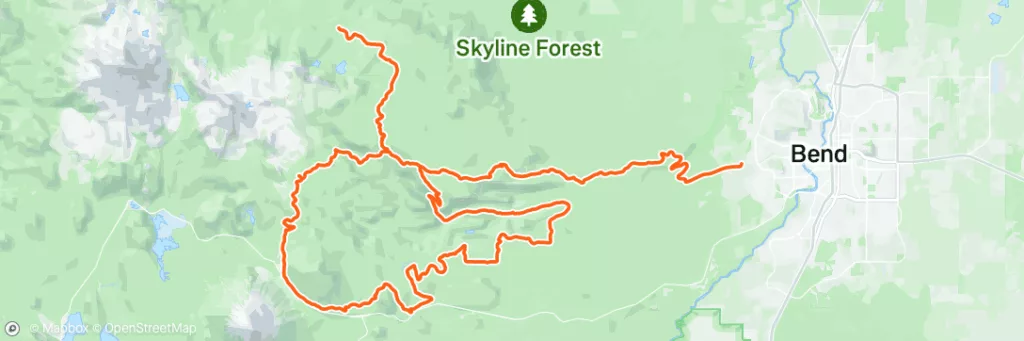

We ran a race of extremes. We ran our fastest mile (8:10) right out of the start line, where the race follows a straight, paved road for two and a half miles. This was more a nod to the shuffling of position that happens early in the race while the field is large and tight. The entire ascent was strong but restrained. And we celebrated our choice of races as we enjoyed the smooth rolling descents on the other side.

Our pauses for foot care are easily discernable at miles 28, 35, and 50. And while our average pace of 13:38 imperiled our 24 hour finish goal, it certainly didn’t negate it. We’ll never know if we would have finished in 24 hours. But, given that almost all of the remaining course was downhill and the night brought cooler temps after highs in the 90s we consider it doable. And of course, our race strategy has always been a conservative start and a strong finish. We had a lot still in the tank when the race director closed the course.

In the end, we did complete a solid 100k. I still think the race director should have just added “k” stamps to the end of the belt buckles and let just have them, but that’s just me really wanting that sweet, sweet belt buckle.

What worked, What didn’t

Like every race, Oregon Cascades is an experiment. We have a hypothesis and execute the best race we can with the data avaialble. Some things worked, others did not:

We spent way too much time at the crewed aid stations.

This was the first race we ever ran with a crew. We had no experience being crewed. Our crew had no experience crewing.

Our crew also have lives of their own, and only arrived the night of the race, just before we went to bed. So, we never had to opportunity for a proper briefing before the race. And while Chris and I are quite efficient on our own on races, coordinating a crew of wellmeaning friends and family is hard to do with 50 miles already under our belts. That said, they were indispensible when it came to foot care. For a runner, bending over to change shoes is no small feat.

Profalactic footcare takes experience but is worth the effort.

The night before the race, we taped our feet with KT-tape around known blister spots to minimize hot spots and avoid a rushed job the day of. We are still getting this technique right. I was happy with my taping but Chris had to stop at the first, fourth, fifth, and seventh aid stations to care for his feet. In the end, preemptive footcare still resulted in some of the happiest feet we have enjoyed at any distance, but better initial taping will hopefully allow us to finish the race with significantly shorter stops at aid stations in the future.

Liquid Calories remain the core of our nutrition strategy.

Ever since Snaketail, we have relied on Tailwind as our main source of nutrients. We usually fill a bunch of hydration flasks with two scoops of Tailwind (200 kCal) and then fill them with water as the need arrises.

These prefilled flasks were a highly effective nutrition solution for both the Snaketail and Strolling Jim. But both of those races were short enough that we could carry enough calories with the bottles we had. But it is cumbersom to carry 8 flasks at at time, even if they only have powder in them. And we only have enough bottles to prefill 1,600 calories of liquid hydration at a time, not the 6,600 we should have to cover 100 miles in 24 hours. So, we planned to refill the bottles at Skyliners and 1514. The result was unnecissarily complicated.

In the future, we need to figure out a more simple way to dispense our powders and only carry three flasks at a time. For most, this means the preportioned sachets sold by Tailwind, but we aren’t fans of how difficult they can be to open on the go. An alternative will take further experimentation.

When it comes to any nutrition, variety spreads the risk.

So many powders for liquid nuturitions bill themselves as the complete package for running nutrition: carbs, salts, maybe even some caffeine. But, the longer you run, the more the shortcomings of any one concoction is amplified and can lead to pallet fatigue. We relied on Tailwind with occasional flasks of Maurtens, cola, and the electrolyte drink provided by the race. I may have gotten tired during the race, but I was keeping up with my calorie plan.

Don’t cary trekking poles if you don’t have to.

While the first 20 miles of the race were uphill, it was a gentle, runnable slope. We opted to pack the poles in our drop bags at Skyliners to pick up for the final big climb and then drop them again at 1514. We never made it to 1514, but we definitely didn’t mind the first 50 miles without the poles and valued them throughout the following 7 mile climb.

Try to avoid races during wildfire season.

The dry fall months can make for some pleasant running, but in regions where wilfires are frequent, it shouldn’t be a surprise that we experienced some smoke. This wasn’t the first running of the Oregon Cascades 100 to experience wildfire smoke, it’s just the first to have the fires so close they had to cancle. It’s hard to invest all that time and money training for a 100 mile race only to have it cancled, even when that was the responsible choice in the face of a natural disaster. Rather than facing the repeated disappointment and in lieu of the punishing training through the summer heat, we’re planning to try our luck at spring 100s in the near future.

I need a better protection for my sides against chaffing.

Balms and bandages just don’t seem to cut it. the chaffing on my sides from the hydration vest was intense. As part of the continuing foot taping experiments, I’ll be testing the effectiveness of taping my sides against future chaffing.

Photography by James Holk for Alpine Running

Final Thoughts

It wasn’t meant to be. We trained for and executed what I still consider to be a solid race strategy. Are there things we would change? Absolutely. But what barred us from the finish line was not our fitness or preparation. It was a natural disaster beyond our control.

Instead, this is a learning opportunity. And I think we have taken away a wealth of knowledge that I look forward to using in our next race.

Photography by Tiare Bowman for Alpine Running