Adams Museum in the gem in the crown of Deadwood, South Dakota. Most every other part of this tourist town is missable but the Adams Museum justifies a detour. This extensive cabinet of curiosities encompasses gold nuggets, taxidermy oddities, antique counterfeiting tools, a plesiosaur, and a nudist colony. Never forget the nudist colony.

The existence of the Adams Museum is thanks to W.E. Adams, who founded the collection in 1930. Adams was a successful business man in Deadwood, finding gold by selling goods to the miners. Its mandate was to preserve the history of the Black Hills. Its continued preservation is credited to the proceeds from the town’s limited stakes gambling.* The funds allowed the museum board to hire professionally trained museum staff. The result is exquisitely documented and displayed collections.

Different corners of the museum’s three stories host a variety of themes celebrating cultures, characters, vice, and industry in Deadwood and the rest of the Black Hills. “Wild Bill” Hickok’s “dead man’s hand” of cards is on display along with ancient fossils and odd inventions.

In the basement level, an impressively complete fossilized skeleton of a plesiosaur is on display. 95,000,000 years ago, South Dakota was part of a shallow sea dominated by plesiosaur. Layers of mud and sand preserved this particular plesiosaur until it was uncovered by Charles C. Haas and his son in 1934. These amateur paleontologists were hunting for shark’s teeth when they encountered some bones in an uplift of sandstone. Painstaking work with just a hammer and chisel revealed a plesiosaur. When early preservation methods began to fail in 1996, a professional paleontologist was contracted to restore the skeleton. Along with his commendable preservation work, Dr. Bruce Schumacher discovered that this skeleton was a one-of-a-kind link between plesiosaurs of two different periods.

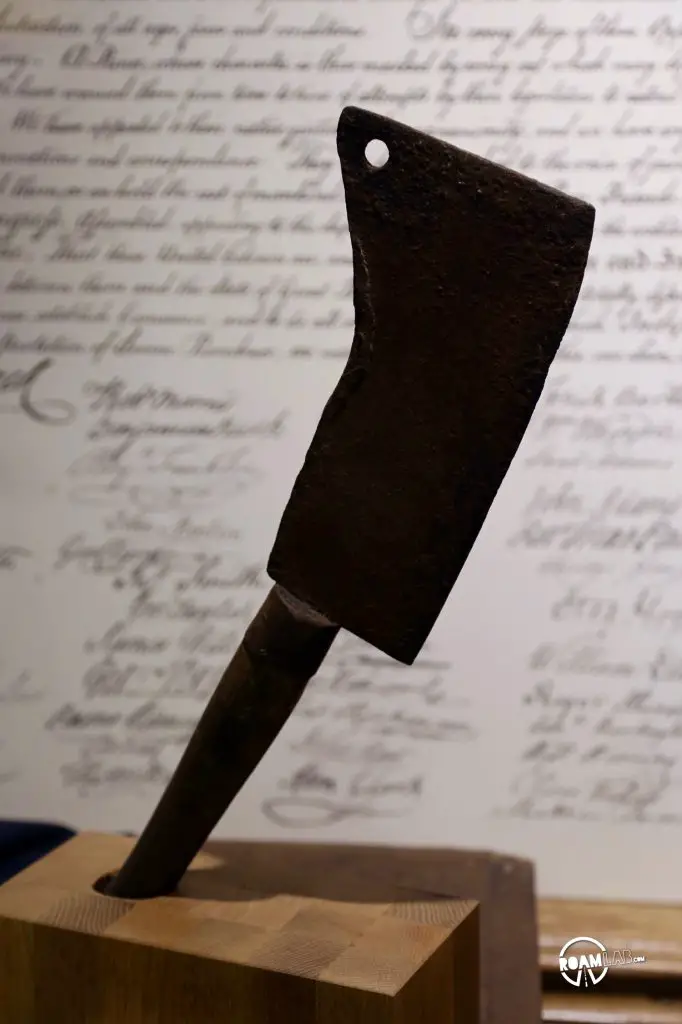

In one nook of the downstairs are items implicated in criminal acts. There is a piece of cement, part of a prohibition era floor where jugs of alcohol could be secreted underfoot and thirsty patrons could dip straws through the floorboards for a drink. There are boots worn by a murderer who attempted to escape justice in Minnesota only to meet his end in South Dakota. Or a cleaver wielded by a murderous employer who barely escaped mob justice only to be found guilty in a court of law and hung.

Arguably my favorite piece in the entire museum is R.J.Poe’s Nudist Colony. Poe worked in the Homestake Mine in Lead, South Dakota where he contracted an infection that culminated in spinal paralysis. With his limited mobility, he found release and expression in carving wooden figurines. His nudist colony of 97 hand carved figures captures a love of motion and the human figure. In a 1937 interview, Poe explained “Carving of movement is a form of escape for me. Whenever I get to feeling logy or dull I grab my jackknife and a chunk of basswood and set to work.” And move his figures did. Between 1933 and 1934, Poe’s carvings were on display at the Chicago World’s Fair. Later, they were donated to the Adams museum where they can still be admired. As one curator notes: “Many suggest a womanhood rather outside the bound of female roles in Poe’s day. These figures are athletic, assertive, unself-conscious and seemingly able to do all that men do…these figures are are striking for their lack of sensuality.”

There truly is something for everyone at the Adams Museum. Children and adults, history buffs and folk art connoisseurs, students of surveying and scandal can all find their favorite piece and learn something new.

*Thank you gamblers. Your loss is our gain!