How Much Power Do I Use In A Day? A day in the life of a truck camper's electric system

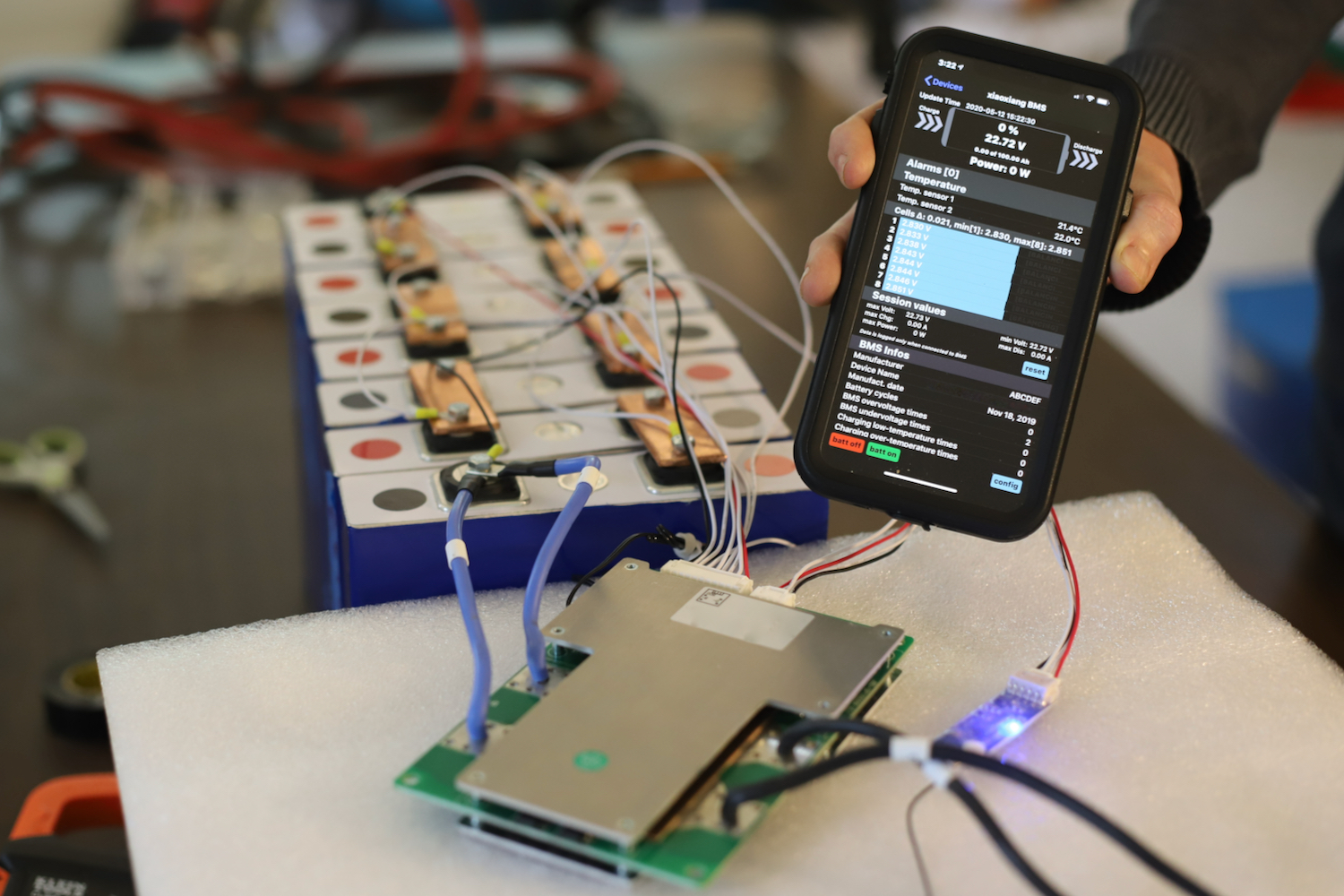

To know how large of an electrical system we need, we must to estimate our consumption. It’s a task that seems simple at first, until you really sit down to think through all the variables. To know our power draw, we need to know what appliances we will be using. There is a vast difference in the power draw between different makes and models of refrigerators , stoves, and microwaves. But we are holding off on buying those high ticket items until we have a better sense of our constraints.* So, this is a process of educated guesses and many rabbit holes. Many of the numbers in this post are derived from much more involved research broken out in other posts. But here is as close to a summary as I, the obsessive documenter, can manage.

Three years ago, I wrote Adding Up The Amps. I have been tempted to take it down or update the post. But instead, I like the idea of leaving it there as an example of how much our goals and intentions change. It is testament to the fact that, with limited space for solar and batteries, one rarely can have too much power. Our ambitions since that post have shifted even more toward extended boondocking and having a fully functional home on wheels. I’m no longer looking at inflexible panels, AGM batteries, and minimalist products. I want a fully functional office and home on wheels for all seasons. Now, I just have to figure out how much power that takes. And build a system to those specifications.

Defining an “Average” Day

In order to estimate our average power consumption, we need a sense of what an average day looks like. What appliances will we use and how long will we use them? There are many ways a day can proceed. That can mean more or less power consumption. Our goal with this build and this particular exercise, however, is to create a mobile work space. So, the camper needs to be able to support us through a 24-hour work day. That means preparing breakfast, lunch, dinner, working on our laptops at the dinette, and occasional trips to the bathroom.

Hot, cold, or cloudy weather cannot be the reason that we miss deadlines or underserve our users. With that in mind, we will split our calculation into two sections. First, the relatively seasonal independent power costs: work, food, and general hygiene.

Our power consumption is potentially different from other RVers. We have a particularly high power draw compared to the average RVer because we have a completely electric system. Heaters, stove tops, and refrigerators that many people power with propane, we use electrical. The approach is particularly for safety, partially for simplicity, and partially for scalability (we believe the future is electric.) In addition, we aren’t work-from-home 9-to-5ers. We run our own business which means long hours on a computer. So, it is worth keeping in mind, if you are looking to apply this post to your own calculations, that you will want to take the time to walk through what your normal day is like and how that would translate into your own calculations.

Table 1: Non-Seasonal Daily Estimated Electrical Consumption

| Products | Watts/Hour | Hours/Day | Daily Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Water Heater | 1/2/3 kW | .25 | 500 |

| Laptops (2) | 50 | 12 | 600 |

| Monitors (2) | 75 | 12 | 900 |

| Stove | 1,800 | .5 | 900 |

| Convection Microwave | 1,500 | .25 | 375 |

| Lights | 28.4 | 3 | 85.2 |

| Water Pump | 65 | .25 | 16.25 |

| Refrigerator | 30 | 24 | 418 |

| Hotspot | 12 | 50 | |

| Cell Booster | 8 | 12 | 96 |

| Water / battery heater | 65 | ** | ** |

| Monitoring System | TBD | TBD | – |

| Security Cameras | TBD | TBD | – |

| Chargers | *** | *** | 181.64 |

| Parasitic Loss | TBD | TBD | – |

| 4122.09 |

**Asterisk values denote power consuming devices that are unlikely to be in use while boondocking. For example, water/battery heater is something that is important when the camper is not in use, but redundant when we are actively living in the camper and using other temperature management solutions.

Factoring in Weather

Unfortunately, one of the greatest energy draws in our system is the heater or the air conditioning. Temperature control with electric power is notoriously power hungry. We are doing our best to mitigate the draw with energy efficient products. We intend to remain in temperate climates—traveling with the weather—where we won’t depend on power hungry temperature control. But surprises happen. Family events, heat waves, business meetings, and general emergencies could have us in extreme temperature zones at times. Hot and cold weather can have a strong effect on your behavior but we can’t stop working just because the climate is sub-optimal. So, there is a strong seasonal component involved in estimating how much power we need.

This is an exercise in defining thresholds. What is the coldest and hottest weather we can reasonably expect to camp in and still be productive workers inside the RV? And how much energy would that require? There are fall backs: a standalone propane heater, stove, or even checking into an RV park or a hotel. But all of these become costly when overly relied upon. So, the goal is to create as resilient a system as possible. What will that look like?

Optimal Weather (72°)

To start, we will begin with the baseline of energy consumed in response to ideal weather. Even optimal weather has its own specific power demands. On a beautiful, 72-degree day with a gentle winds, the windows will be open and the fan running. It’s not a lot of power needed, but it is power and it adds up.

Table 2: Good Weather (72°) Daily Estimated Electrical Consumption

| Products | Watts/Hour | Hours/Day | Daily Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fan | 60 | 12 | 720 |

| 720 |

Winter

In the winter, we don’t expect to be able to work in shorts and a t-shirt but we do need some temperature control. With warm slippers, cozy robes, and cuddly blankets, we can take a bit of chill in the camper. But we can’t work with gloves on. So, winter temperatures come down to how cold the camper can be where we can still be productive workers—typing on our computer.

Table 3: Winter Daily Estimated Electrical Consumption

| Products | Watts/Hour | Hours/Day | Daily Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heater | 231 | 6 | 1386 |

| 1386 |

Summer

Most summers, we head for higher latitudes and elevations. But sometimes we get stuck in the heat. In these scenarios, we have an air conditioner, large windows, and a fan. In the night, we will open the windows and run the fan to fill the camper with cooler air. In the day, we will close up the camper against the heating air and run the air conditioner in the heat of the day. Granted, the wattage listed assumes the air conditioner is running full blast. So, our goal is to keep the total period of time when the air conditioner is cycled on to 1 hour a day. Any more, and we have to either move to somewhere with shore power or find somewhere else to be during the hottest points of the day.

Table 4: Summer Daily Estimated Electrical Consumption

| Products | Watts/Hour | Hours/Day | Daily Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Air Conditioner | 440 | 1 | 440 |

| Fan | 60 | 8 | 480 |

| 920 |

Which Season Needs the Most Power?

Now that we have a break down of non-seasonal power consumption and seasonal power consumption, we can add them up to get an insight into what is our most demanding scenario. I suppose it’s not surprising that winter looks to be the most demanding season. Electric heaters are notoriously inefficient. All the same, we have our number now: 5,508 watts.

Table 5: Estimated Electrical Consumption Seasonal Spread

| Weather | Non-Seasonal (watts per day) | Seasonal (watts per day) | Total (Watts/day) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Optimal | 4122 | 720 | 4842 |

| Winter | 4122 | 1386 | 5508 |

| Summer | 4122 | 920 | 5042 |

What’s Next?

Now that we have an average number of watts determined, the real work can begin. We have an electrical system to spec out and install. These numbers will inform the number of batteries and solar panels we buy, the strength of the system we build, and even the wiring we will need.

Did you design your own electrical system? What lessons have you learned from your RV’s electrical system? Let us know in the comments!

*Read Shopping for an RV Refrigerator to dive deep into the challenges of balancing the capabilities I want and the power load I can afford.

***Batteries Not Included

Most of our tables represent components that have time based power draws. How long are the lights on? How long will we run the stove? But, on the other side of our calculation is items that are often overlooked: battery powered items. These need charging too. The variable here is: how often?

Our threshold when calculating the power needed for battery powered equipment is the lifespan of a single battery charge. For example, our CO monitor is battery powered but those batteries are designed to last 10 years. Any batteries that can last a week or longer without needing to be recharged are not considered a significant part of our calculation. So, security cameras, flashlights, and infrequently used devices are not part of the calculation. But phones, cameras, and headphones are things I use on a daily basis and charge frequently.

Wattage Totals For General Chargers section on table 1

| Products | Battery Capacity (mAh) | Battery Voltage (V) | Battery Energy (Wh) | Total (Wh) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Camera | 1865 (2) | 7.2 | 14 | 28 |

| Drone | 3830 (2) | 11.4 | 43.6 | 87.2 |

| Drone Handset | 2970 | 3.7 | 11 | 11 |

| Drone Headset | 9440 | 3.8 | 35.44 | 35.44 |

| Headphones | 520 | 5 | 14 | 14 |

| Phones (2) | 2900 (2) | – | – | 6 |

| 181.64 |