While Cuyuna Country State Recreation Area is best known for its mountain biking trails, a visit to this wild, reclaimed land would be incomplete without spending some time on the many lakes scattered across the area. Granted, they aren’t natural lakes, the are flooded former open pit iron mines. While most evidence of Cuyuna Country’s mining past has been removed during the reclamation process, the pits themselves remain and make for ideal water recreation, including fishing, boating, scuba diving, and paddling. After a short mountain bike ride and setting up our camp at Portsmouth Campground, we break out our rafts and life vests for an evening paddle around Portsmouth Mine.

Portsmouth Mine Landscape and Paddling Conditions

Portsmouth Mine is representative of most of the open pit mines found across Cuycuna Country. The rich red dirt banks undulate between gentle grades–where the shallow water is crowded with reeds–and steep, exposed red earth bluffs shaded by aspen forest. The water is remarkably clear and smooth allowing canoers, kayakers, SUPers, and rafters to glide over forests of submerged timber, lush green aquatic plants, even concrete pads, remnants of buildings that supported the mining operation.

Portsmouth Mine Facilities

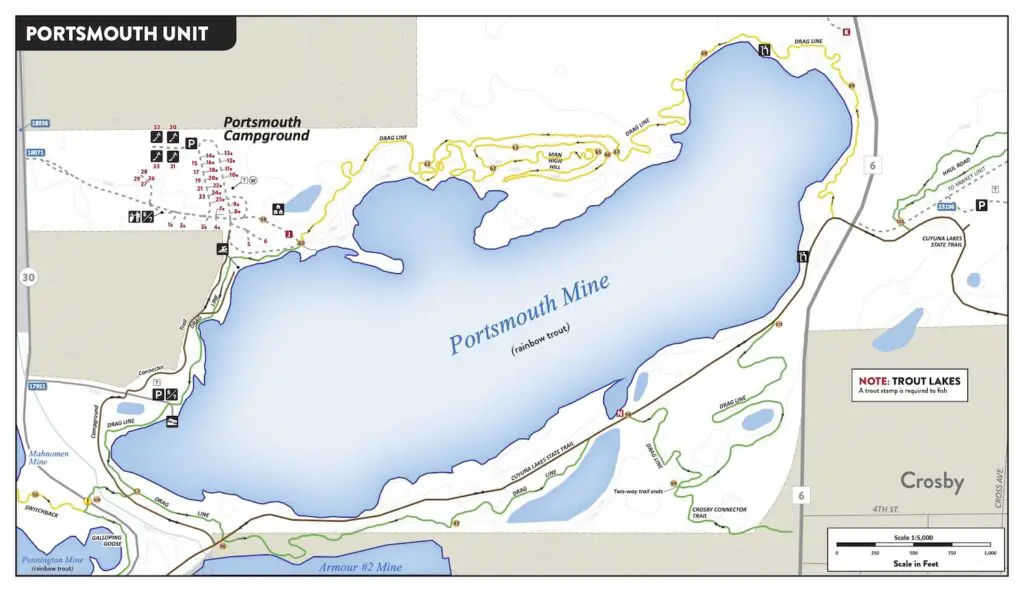

As noted before, there’s no shortage of ways to enjoy the calm waters of this flooded mine. There is a boat launch on the western edge and the mine is stocked with rainbow trout. On the north shore, near the Portsmouth Campground, there is also a swimming beach that can double as an easy entry point for light watercraft, including our rafts.

Our Experience

Since we began our journey down Minnesota’s Great River Road, there’s one activity that we have glaringly missed: paddling. While the Portsmouth Mine is not part of the Mississippi, it does help scratch that itch. A poor weather forecast delays our initial launch, but after waiting for a non-existent rainstorm over a couple of hours, it is getting late and we are getting anxious. So, we inflate our rafts, assemble our paddles, don our life vests, and carry our gear to the nearby swimming beach to launch into the water.

We consulted a ranger that afternoon about where to paddle. Her main advice is to stick close to the shoreline where we can see through the clear water to the floor. There is ostensibly a collection of concrete pads, remnants of the previous mining operations. But wherever they actually are, we do not spot them. Instead, we are swept away by the enticing landscape and wildlife.

This is a sculpted terrain. As a former open pit mine, trucks and equipment would have to be driven down to the mine’s floor to move the displaced earth and process the iron ore. We paddle by shallow reeded stretches that were likely graded land, accessible by vehicles, along with steep exposed red dirt bluffs that were likely cliffs formed over decades of mining. Here, in particular, we encounter what might as well be a submerged forest. Trees that have given way to the seasonal erosion of the bluffs have tumbled into the water below. We skim over barely submerged tree trunks in a submerged forest.

Floating on Portsmouth Mine

From the beach, we paddle along the north shore of the flooded mine, a fairly wild stretch of reclaimed forest. We know the Drag Line mountain bike trail winds by just north of us, but it is set deep enough into the woods that we don’t see any evidence of development. Instead, we get a delightful dose of wildlife.

This is the evening, after all, a prime time for wildlife viewing when the heat of the day has dissipated and soft light still illuminates the water and forest land for animals to hunt and forage. Our first encounter is a flock of ducks. I attempt to not disturb them while taking a picture, but nothing quite says “inconspicuous” like a bright yellow raft. While the ducks may have taken wing, I am lucky enough to take their picture. And that feels like an accomplishment enough to justify the day. But in truth, we were only getting started.

Oh Dam

After coming around a large outcropping, I wave Chris down: it’s a beaver dam. And, as far as I can tell, it’s being maintained. Bobbing along the shore, we see gnawed wood signatures of the voracious aquatic mammal. And then we hear it: a nearby bush rustles as something inside chomps on a branch. Could we be so lucky? We wait with bated breath. The bush goes silent. We doubt ourselves. Maybe it is all in our heads. The chomping resumes, and so does our anticipation. The cycle continues for minutes on end until the leaves part and we spot the toothy culprit: it’s a squirrel.

We chuckle at our own over-eager imaginations and paddle onward.

It’s a Wild Life

But just as we start to think that maybe, just maybe, this trip won’t yield a National Geographic moment, it happens. Chris points skyward where an osprey is on an aerial hunt, its eyes locked on some unseen prey. Moments later, it ascends with a fish clenched in its talons. I miss the shot with my camera, but the moment remains with us.

Full Circle

As we loop back towards our starting point, our mystery mammal arrives. It’s a beaver, swimming with a sense of purpose and agility. Its head bobs just above the waterline, perfectly at ease in its domain.

Satisfied with this unexpected encounter, we return to shore. The rafts are deflated, gear stowed, and a profound sense of accomplishment. We have seen so much. And know that tomorrow there will be even more.